Wedgwood is synonymous with the pottery industry of Staffordshire to such an extent it is hard to grasp how far and fast it changed two and a half centuries ago.

Most of that change was the achievement of one man, Josiah Wedgwood, albeit aided by many others in different ways.

Pottery has been manufactured in Staffordshire for many hundreds of years. A type of red-clay earthenware archaeologists call Stafford ware has been found at many excavated sites across the Midlands, suggesting the town was an important pottery-making centre in Saxon times, well before the Norman Conquest.

Mediaeval potters learned how to glaze their pottery with simple chemical coatings using salt or lead compounds added during the firing of the raw material which occurs abundantly here. The earliest record of a potter in Stafford occurs in 1275.

Usually only fragments of these forms of pottery survive. Entire pieces of pottery survive from the 17th and early 18th centuries, but these are still crude and rustic compared to works of art being produced in North Staffordshire by the late 18th century.

From 1720, earthenware was whitened by adding ground flint to the wet clay before firing. The later transformation of the potter’s craft into works of art owed much to Josiah Wedgwood.

Josiah was born into a family of potters and farmers in Burslem in 1730. His father, grandfather and great grandfather had all supplemented their income from farming the clay soil of the area by making pots. But the Wedgwoods had more substantial relatives who had inherited land at Herracles Hall, near Leek, in the late 15th century.

At the age of 12, Josiah was struck by smallpox, a viral infection which was declared eradicated from the human race in 1979 but was then a killer. Four out a five children infected died of the disease and survivors were often left scarred by the rash of pustules it produced on the skin.

One third of all cases of blindness were attributed to smallpox and a small proportion of sufferers developed deformities in their limbs.

Josiah survived, did not go blind and his complexion does not appear to have been severely disfigured. But the disease left him with a weakened right knee, which eventually led to his lower leg being amputated.

Even this turned out to be a blessing in disguise.

The long illness gave him time to improve upon his rudimentary education, which had been cut short by the death of his father in 1739. He read avidly and his curiosity grew.

His weak knee left him unable to work the pedal which turned the wheel on which potters threw their wares. But he was able to explore every other aspect of the potter’s craft and this had far-reaching consequences.

Josiah’s elder brother, Thomas, was unwilling to grant him a partnership in the family business and so he went to work in Stoke-upon-Trent for John Harrison. There he specialised in turning out pots and figurines in clays of variegated colours known as “tortoiseshell” or “agate”, as well as the traditional salt and lead glazes and slipware, in which the body of a piece was coated in liquid clay before firing.

(One of the reasons North Staffordshire was so suitable for the production of pottery was the ready availability of raw materials – local clay, Derbyshire lead and Cheshire salt for glazing and Staffordshire coal for firing.)

In 1754, Josiah went into partnership with a major manufacturer for the time, Thomas Whieldon, of Fenton Hall. Whieldon encouraged Josiah’s taste for experimentation, which was just as well because tastes were changing and customers were looking for something more than the traditional pottery being made.

His innate curiosity and renewed illness led Josiah to conduct more experiments until on May 1st, 1759, he took a lease on Ivy House in Burslem. He now had his own factory.

Demand for the traditional variegated colours was flagging, so Josiah set out to solve a long-standing problem: how to ensure that plain creamware pottery was of a consistent quality.

All potters were familiar with problems such as cracking or crazing of glazes when the chemical mixture or firing temperature of the kiln were not right. Creamware posed the added problem that the hue could vary from butter yellow to almost pure white, when the customer wanted uniformity.

Part of the solution was to make his workmen specialise in individual tasks rather than complete each pot or batch of pots themselves. A very early form of production line was born.

Early in 1762, Josiah suffered another bout of pain and inflammation in his knee and was forced to recuperate in Liverpool. There he met a man who knew hot to make full use of Wedgwood’s ingenuity – Thomas Bentley.

Born in Derbyshire in 1730, the same year as Wedgwood, Bentley had a much longer formal education and had set himself up as a merchant in Manchester, then a growing industrial town. Later he moved to Liverpool, a flourishing port through which the Staffordshire potteries imported much of their clay.

Bentley was much better connected than Wedgwood and was able to introduce his new friend to many acquaintances from the worlds of art and science. The two hit it off immediately, something which again had far-reaching consequences.

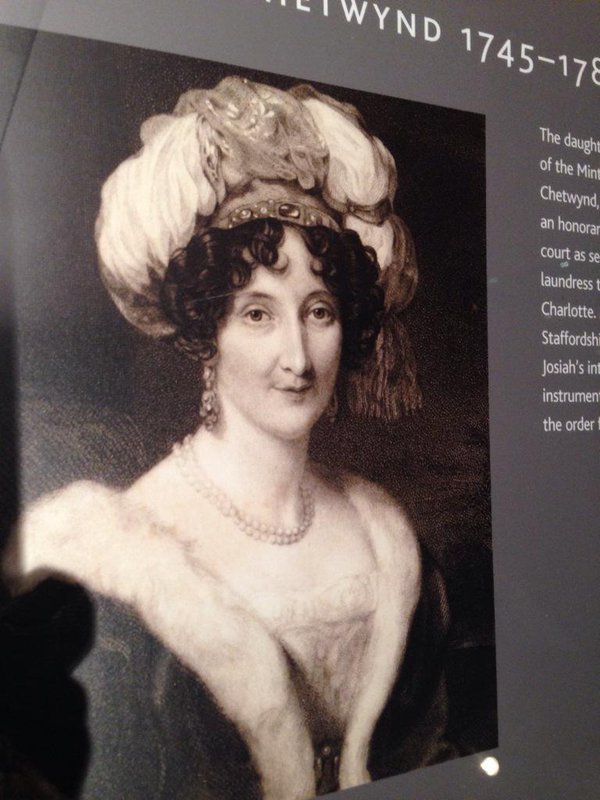

Among Wedgwood’s Staffordshire acquaintances were the Chetwynds of Ingestre. The Hon. Deborah Chetwynd was the daughter of the third Viscount Chetwynd and a maid of honour (equivalent to a lady in waiting today) to Queen Caroline, consort of King George III.

Miss Chetwynd told the Queen abut Wedgwood’s creamware which resulted in an order for twelve tea cups, coffee, cups, sauces and associated tableware for the Court of St James’s in 1765.

Although Wedgwood was by no means the only Staffordshire manufacturer of creamware, he was the only one authorised to style himself “Potter to Her Majesty”. The public relations value of landing this one relatively modest order was colossal.

Before long, some very distinguished visitors came to Wedgwood’s Burslem works to view his wares for themselves. They included the fourth Duke of Marlborough, the second Earl Gower and the first Earl Spencer. Wedgwood was the leading pottery firm in Staffordshire.

Wedgwood had already met Lord Gower in connection with improving road links to the Potteries. The turnpike trusts were a major innovation of England’s roadwork networks, enabling private investors to charge tolls for the use of the roads they improved, many of which had hardly altered since the Romans built them more than a thousand years earlier.

For manufacturers of a fragile commodity like pottery, finding a safe and reliable means of transport was a priority.

Gower was head of the Leveson-Gower (pronounced Looson-Gore) dynasty descended from a Yorkshire family of baronets and the mercantile Levesons of Staffordshire. The second earl was Lord Lieutenant of Staffordshire, Lord President of the Council (a senior Cabinet post) and brother-in-law of the third Duke of Bridgewater.

Gower had already helped draw up a petition to Parliament for a bill to link Burslem to an existing toll road in North Staffordshire. Such bills were commonly sought to facilitate the construction of roads and later canals and railways. (The HS2 high-speed railway line through Staffordshire is also the subject of one now.)

The Duke of Bridgewater had started the canal craze by building a waterway to transport coal from his mines at Worsley to Manchester. Not only were people amazed to see narrow boats travelling on an aqueduct way above their heads, they were even more surprised when the cost of the coal they carried was halved.

Wedgwood had long wanted to speed up and cheapen the carriage of fine clays from the West Country which were needed for creamware. He became an enthusiastic supporter of the proposed Grand Trunk Canal linking the River Trent in Staffordshire to the River Mersey in Lancashire. The Trent itself is navigable as far as Derbyshire and a 94-mile artificial waterway was needed to make the link.

Gower chaired a public meeting to drum up support for the project, at which he spoke enthusiastically in its favour, in January 1766. Wedgwood helped steer the bill through both Houses of Parliament until it received Royal Assent on May 14th of the same year.

Wedgwood was then appointed treasurer and unofficial banker to the shareholders of the £130,000 scheme. A bill to promote the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal, linking the Trent and Mersey to the River Severn, was passed the same year so the funds were soon found.

One of the main obstacles the 11-year project had to overcome was Harecastle Hill, near Kidsgrove, between the Potteries and the Cheshire border. The engineer, James Brindley, drove a literally ground-breaking tunnel through the landscape in a process which unearthed fossils he sent to Wedgwood to satisfy his scientific curiosity.

(Another leading figure in the enterprise was Thomas Sparrow, of Bishton Hall, near Stafford, who was clerk to the company shareholders. Wedgwood would sometimes stay at Bishton as Sparrow’s guest.)

By 1767, Wedgwood was consulting Bentley about anything and everything, including the fossil bones unearthed at Harecastle. The following year they entered a formal business partnership in which Wedgwood concentrated on manufacturing and Bentley on marketing the creamware which was by now a runaway success.

But Bentley was more than a marketing man. His keen sense of what would sell led him to put ideas into Wedgwood’s head, leaving his scientific brain to overcome any production difficulties.

By this time, foreign markets were opening up to Wedgwood and Bentley, as the firm became known and it was from overseas that new inspiration came.

The British envoy to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (southern Italy) was Sir William Hamilton, a Scottish aristocrat who spent much of his abundant spare time collecting classical pottery and reporting minor volcanic eruptions of Mount Vesuvius in his diplomatic despatches from the court of Naples to London.

In 1738 the astonishingly well-preserved remains were discovered of the ancient Roman town of Herculaneum, which had buried by a pyroclastic flow of superheated gases from Vesuvius in AD79, during the same volcanic eruption which buried Pompeii in ash. The discovery caused a sensation in cultivated society throughout Europe – classical studies still being the bedrock of most education.

Hamilton published a book of his studies entitled Etruscan Antiquities in 1767. The title was a misnomer because the Etruscans were a pre-Roman civilisation north of Rome itself, in the region now known as Tuscany.

However, the name stuck and Wedgwood set about producing vases based on ancient Roman and Greek designs. For this he would need a new factory designed on a wholly now concept and it was to be called Etruria, after the kingdom of the Etruscans.

Wedgwood bought a 350-acre estate called the Ridge House in Burslem and had the planned route of the Trent and Mersey Canal altered to run immediately past the new factory. It was opened on July 13, 1769.

He also sought new showrooms for his wares in London and opened an enamelling workshop in Chelsea.

Hamilton’s brother, Lord Cathcart, was British ambassador to the court of Empress Catherine the Great of Russia, at St Petersburg. In 1773, through Cathcart’s good offices, the Empress sent Wedgwood a commission for a gigantic creamware dinner service of 932 pieces.

Each piece was to be adorned with the frog motif of her Chesman Palace, the name meaning “frog marsh” in Finnish – that being the language of the region Czar Peter the Great had conquered for his new capital. Each major piece was also to bear a landscape painting of a different English country house.

It was a demanding commission and Wedgwood had to find 1,244 drawings or paintings of a large number of country houses. From Staffordshire, these included Etruria Hall – Wedgwood’s new home – Ingestre, Keele, Shugborough, Swynnerton and Trentham.

Wedgwood had some trial pieces made and fired in the kiln before firing the main service for the Empress. A dessert plate is still on display at the Wedgwood Museum in Barlaston, Stoke-on-Trent.

A bowl with lid is on display at Shugborough. Variously described as either a dessert bowl or small soup tureen, it measures 21cm (over eight inches) across, from handle to handle, and 15.5cm (over six inches) from the top of the lid to the foot of the bowl.

The view of the Shugborough estate appears to show Essex Bridge across the River Trent on one side and Richmond Castle, Yorkshire, on the other. A church tower on the lid looks suspiciously like that of St Michael’s and All Angels’ Church, Colwich, where many Ansons are buried.

Somehow the imperial dinner service remained undiscovered at the Hermitage museum in St Petersburg until the late 20th century. Now the surviving pieces, nearly 800, are on public display there.

Finished in 1774, the service cost the Empress approximately £3,000 (nearly £400,000 at today’s prices) – a colossal sum in the 18th century and rather more than Wedgwood had estimated. None the less, the Empress paid promptly and without demur.

Before being exported to Russia, the service was displayed at Wedgwood and Bentley’s London showrooms, taking up four rooms altogether. Queen Charlotte was only one of hundreds of people who came to view it – another triumph of public relations.

By 1775, Wedgwood had perfected the fine and durable pottery he needed to reproduce the artefacts of ancient Greece and Rome. It had a mat finish, usually of pale blue or green but also black, with white figures applied to the surface. He called it “jasper”.

Today this is the quintessential Wedgwood product, although he continued to produce many other forms of pottery.

By now Wedgwood was producing such a variety of pottery, both ornamental and utilitarian, that he and Bentley found it necessary to publish their first catalogue. Customers no longer needed to go to London or Etruria to see what the partnership had to offer.

The artist George Stubbs spent months at Etruria experimenting in pottery and produced a set of horse studies in jasper. He also painted a family portrait of the Wedgwoods. Further proof of Wedgwood’s eminence was provided by the society portrait artist Sr Joshua Reynolds who painted his portrait.

Political controversy enveloped Wedgwood when a rival manufacturer, Richard Champion, attempted to obtain an Act of Parliament giving him a monopoly of West Country clay for porcelain.

Largely through the influence of Lord Gower in the House of Lords, a compromise was reached. Champion was allowed a monopoly for his porcelain mixture but other manufacturers were able to use the raw materials for their own products.

Wedgwood had an ambivalent attitude to politics. He was an astute judge of public affairs, opposed the war against the rebellious American colonies, favoured union of Great Britain and Ireland and supported parliamentary reform. But he never dabbled in party politics.

Not until 1832, after his death, were the Potteries given their separate representation in the House of Commons. His son, John, was then elected as one of Stoke-on-Trent’s two Members of Parliament.

The one issue on which Wedgwood was outspoken was the abolition of slavery. The courts had ruled slavery illegal in England but the ruling did not apply to British colonies. British ships did a flourishing trade in transporting slaves from Africa to the Americas, to the horror and dismay of many, including Wedgwood.

A jasperware cameo showing a manacled Negro slave with the superscription “Am I not a man and a brother?” was a popular product of the factory at Etruria. He sent a copy to the American statesman Benjamin Franklin. Slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1807 and the trade ended in 1833.

Tragedy struck Wedgwood in November 1780 when Thomas Bentley died suddenly after a short illness. Bereft of his mentor, Wedgwood had to market his wares on his own. His name was well enough established for this to be possible.

Further recognition came in 1783 when Wedgwood was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. His paper on the pyrometer – a thermometer capable of measuring the very high temperatures needed in a pottery kiln which he had invented– had been read to other fellows the previous year.

Wedgwood never entirely retired from business but he began to take a back seat after 1790, the year he turned sixty. By then he estimated the annual value of his factory’s output at £250,000 – twenty-five times what it had been when Etruria was established twenty years earlier.

Josiah Wedgwood died on January 3rd, 1795 but the Wedgwood name lived on. Josiah Wedgwood and Sons remained a family firm until 1950 – spanning nine generations, of which Josiah was the fourth. No other family business has achieved such longevity.

The pottery industry has had its ups and downs in North Staffordshire. Many famous names have disappeared.

But the most famous of them all remains Wedgwood.

Over 250 years of history make Wedgwood a truly iconic English brand. From it’s beginnings in Stoke-on-Trent, and with a heritage of providing Royal Families, Heads of State as well as celebrities and families all over the world, Wedgwood has the expertise, the design and the craftsmanship to create beautiful works of art whilst adorning dining tables with the most stunning of tableware anywhere in the world.